WHAT ARE WE PALPATING?

What are we palpating when evaluating the shoulders of patients with myofascial pain syndrome?

Through palpation, you can feel your patients’ tissues with your hands during a physical examination. The health care provider touches and moves the patient’s body to look at the size, consistency, texture, location, and tenderness of an organ or body part, and how it moves and feels. When you use palpation, you apply a mechanical pressure to the skin in a certain way for a certain amount of time. People’s skin, superficial fascia, and deep fascia can be moved by palpation, but no studies have investigated how reliable and valid it is. Still, healthcare providers use palpation to look at how the fascia system moves.

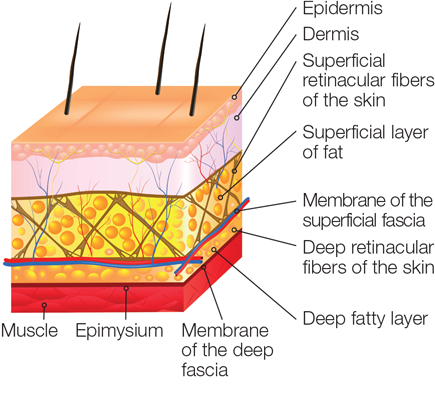

Connective tissues under the skin, mostly collagen, form a three-dimensional web called the fascia system (Figure 1). It helps muscles and other body parts move and stay in place. Fascia comprises both superficial and deep fascia. It starts from the skin and goes all the way to the bones. It goes through and around the muscles, allowing the body to move in a coordinated way. The skin is the largest part of the body exposed to the outside world. The fat-filled superficial fascia comprises collagen and elastic fibers under the skin. The fat-free deep fascia wraps around the muscles. Collagen bundles are a movable structure that enables the body to move in subtle ways. The collagen bundle makes it easy for the fascia to slide over the other layers without causing friction.

Source: Human Kinetics An Employee-Owned Company (2022). What are fascia? (1)

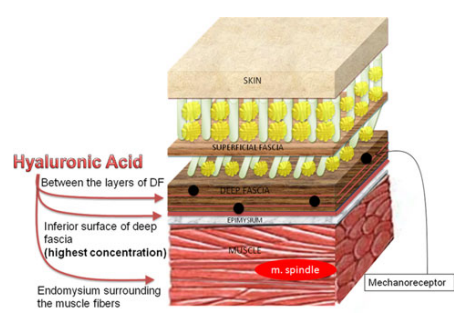

Hyaluronan is a substance found in the upper trapezius fascia system (Figure 2). It is a glycosaminoglycan with a high molecular weight that, when reduced, inhibits fascia displacement, which is related with musculoskeletal pain (2).

Source: Stecco, C., Stern, R., Porzionato, A., Macchi, V., Masiero, S., Stecco, A., & De Caro, R. (2011). Hyaluronan within fascia in the etiology of myofascial pain. Surgical and radiologic anatomy, 33(10), 891-896 (2)

A perceptible distance of >0.05 mm was found for deep fascia displacement (3). None of the people who participated in the study were good at palpating things smaller than 0.05 mm. When someone moves their neck, the therapist should feel for the direction of the fascia system’s movement. The literature doesn’t say whether the fascia movement is palpable (3,4).

Myofascial Pain Syndrome (MPS) is a chronic pain condition characterized by decreased range of motion, muscular weakness, and loss of function in the shoulders and cervical area (5). A clinical manifestation of MPS is reduced cervical range of motion (cervical LOM). In the shoulder and cervical region, pain, tightness, or a local twitch response accompanied cervical LOM (6). Myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) found in MPS are related to fascia adhesions associated with mobility limitation, resulting in cervical LOM (7,8). Participants with MPS have MTrPs (Touma et al., 2021). Fascial adhesions are related with MTrPs, which establish a new line of tension inside the fascia, limiting its mobility. The fascia system moves distinctly in MPS.

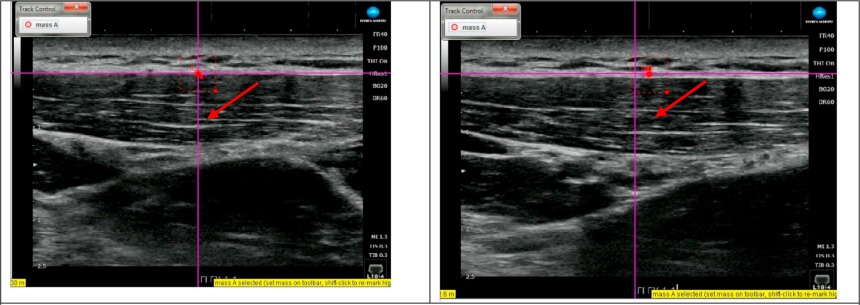

Through the Windows Media Player, we investigated 541 musculoskeletal ultrasound videos for the skin, superficial, and deep fascia displacement per cervical active range of motion of the 299 participants. Of the 299 participants (126 non-MPS: 173 MPS) examined, 182 (61%) were females. The median age was 36 (28-43) years old. The pain duration of the 173 MPS participants was 1 to 12 months. The MPS participants reported taut bands, muscle cramps, tenderness, pain, or discomfort on at least one shoulder. The participants felt restricted cervical movements. The non-MPS participants showed unrestricted cervical movement and non-painful shoulders. We excluded in the study those participants with cervical whiplash, stress headache, fibromyalgia, and chronic regional pain syndrome. Pregnant women or mothers who breastfed in the past six months were also excluded.

For skin, 3,548 of 3,588 musculoskeletal ultrasound videos showing skin displacement were tracked. 3,574 of 3,588 musculoskeletal ultrasound videos showing superficial fascia displacement were followed. 3,522 of 3,588 musculoskeletal ultrasound videos showing deep fascia displacement were tracked (Figure 3). We found a strong accuracy between palpation and skin displacement during active cervical flexion and extension. However, palpation, superficial fascia, and deep fascia displacements showed only weak to moderate accuracy. During active cervical lateral flexion and rotation, palpation, skin, superficial fascia, and deep fascia displacements showed moderate accuracy.

Source: Dones III, V. C., Tangcuangco, L. P. D., & Regino, J. M. (2021). The reliability in determining the deep fascia displacement of the upper trapezius during cervical movement: A pilot study. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 27, 239-246 (9).

There was a strong agreement between palpation and musculoskeletal ultrasound videos on Windows Media Player when determining the direction of skin displacement during cervical flexion and extension. Skin palpation during cervical flexion and extension can be used in evaluating patients with MPS. There was a moderate agreement between palpation and musculoskeletal ultrasound videos on Windows Media Player when determining the direction of the skin, superficial fascia, and deep fascia displacements during cervical lateral flexion and rotation. It is unclear what fascia system was evaluated when shoulders were palpated at the end of cervical lateral flexion and rotation.

References

1. Human Kinetics An Employee-Owned Company. What are fascia? [Internet]. 2022.

2. Stecco C, Stern R, Porzionato A, Macchi V, Masiero S, Stecco A, et al. Hyaluronan within fascia in the etiology of myofascial pain. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011 Dec;33(10):891–6.

3. Kasparian H, Signoret G, Kasparian J. Quantification of Motion Palpation. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015 Oct 1;115(10):604.

4. Nelson KE, Sergueef N, Lipinski CM, Chapman AR, Glonek T. Cranial rhythmic impulse related to the Traube-Hering-Mayer oscillation: comparing laser-Doppler flowmetry and palpation. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2001 Mar;101(3):163–73.

5. Jafri MS. Mechanisms of Myofascial Pain. Int Sch Res Not. 2014 Aug 18;2014:1–16.

7. Mauntel TC, Clark MA, Padua DA. Effectiveness of Myofascial Release Therapies on Physical Performance Measurements: A Systematic Review. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2014 Jul;6(4):189–96.

8. Shah JP, Thaker N, Heimur J, Aredo JV, Sikdar S, Gerber LH. Myofascial Trigger Points Then and Now: A Historical and Scientific Perspective. PM R. 2015 Jul;7(7):746–61.